Seven 🇺🇦 Poems a Week. Week 2: Artur Dron

Artur Dron, call sign ″David″ Territorial Defense Forces

This is a part of the “Seven Ukrainian Poems A Week” project: translations of modern Ukrainian poetry, one poet/7 poems a week.

Grandma Don’t tell me where you are. Tell, there, where you are, did they threshed the wheat? They say on the news, in Donbas, there will be no harvest. But grandpa didn’t believe, so I, too, didn’t believe. September first is as September first always is. The little ones went to school, the little one to kindergarten. I cried at first, didn’t want to go the ceremony. But the grandpa went, so I, too, went. Because I keep crying, you know. The little ones had their suits, the little one her bow. But for this year’s September, somebody doesn’t have a suit. And somebody doesn’t have what to cry with. And somebody doesn’t have grandchildren anymore. Oh God. Don’t tell, don’t tell where you are. But there, whenever you are, have the rains started? We had one yesterday but not a heavy one. A light rain. So light, you can take a child by the hand and go with the child down the road. * * * “on 25th and on 7th” — alternative dates for Christmas (Dec 25th, like Europe, which Ukraine started to observe recently, or Jan 7th, imposed by Russia) We argued again when we should meet you. But, you know, both on 25th and on 7th, Bethlehem was shelled and bombed. There is no crib, no lambs, no perinatal center, no kindergarten, no playground. When you grow up and learn to talk, tell your mother to tell mine how she can live through all of this. Kiryuha “Kiryuha” is an informal version of the name Kyrill “Chudo Market” (literally "Miracle Market”) is a very cheap and very widespread supermarket network You wouldn’t say: were here. Huddled to each other in captured russian dugouts. And the snow came later. We were here, but they would never ask about this. And only Kiryuha, the son of our regiment (how she called him), our only child on the entire street, will once remember broken snickerses and the frost of the dreadful wartime December. Be prepared, they’ll ask other questions, be prepared. Where is your leg? Where are your merry friends? Where is your youthfulness, elderly twenty-year-old human, who still dreams about death and broken snickerses? But they wouldn’t ask about the main thing. Where were you when St. Nicholas in the dreadful wartime December placed by Kiryuha’s bed a bag from “Chudo Market” and there were our snickerses and tangerines. With seeds, but sweet. * * * I saw that the vase with fresh flowers had fallen. “Let me fix this,” — I said to the photo on the cross. I put the vase straight, and saw a note. “Happy anniversary, bunny. Love you.” Izyum communion ...this is my body, which is broken for you for the forgiveness of sins. From Divine Liturgy These are our bodies, that are broken for us. But no forgiveness of sins. These are our bodies, that sometimes are easily broken when pulled from under the ground. Here are our forests, and here are our crosses. And here are bodies that are broken only for us. Now you can see: we are like your son. But no forgiveness of sins. Listen: the same scream, the same silence. That’s how izyum communion looks. Here are our forests, and here are our crosses, and the living dig out the dead and say: these are our bodies, these bodies are ours. We are so like your son. These are our bodies, look, these bodies are ours. We’ve been like your son for a long time. So many bodies, look, so many bodies. We are your youngest son who will never forgive anybody for this. * * * , but why are you calling me that? She will ask. Why do you call me a city? You always write about a city, and I know, it is about me. You write about buses, and my hand starts itching. You write about train stations, and I wake up in the middle of the night and can’t fall asleep. You write about cobblestones, and I feel a lump in my throat that I can’t cough out. Would be so nice to know why you call me a city. When she frowns barely noticeable tramway tracks appear above her brows. Would be so nice to not disembark at the end of the line. Children When we talk about hope actually we are talking about children. I am thankful because the memory of you still climbs out from the inside despite all the time that has passed since. And some day all the children would be squinting from the sun. And those of us who will survive will see that all of it wasn’t in vain. We seldom talk about hope here, or about patriotism, or about the Motherland. But when we do, it is always about children. And, you know, when I think of you now I imagine what child you have been. How you were squinting from the sun. Those of us who will survive would be silent for a long time. Because why do you need words about hope when it is beside you. It stands in stained shorts, scratches its hands bitten by mosquitoes shows its milk teeth to the sun.

Author: Artur Dron, call sign “David”

Interviews (in Ukrainian): TvoeMisto.tv, Vogue Ukraine (notes from the battlefront);

A couple of translations by Hana Leliv: The First Letter to the Corinthians, The Mother;

The Ukrainian War Poetry project has two of his poems translated and read in English.

Poems In Ukrainian

Баба Не кажи, де ти є. Скажи, чи там, де ти є, змолотили пшеницю? Я чула в новинах, що на Донбасі не буде жнив. Але дід не повірив, то і я не повірила. Перше вересня як перше вересня. Малі пішли в школу, мала у садочок. Я переше плакала, не хотіла йти на лінійку. Але дід пішов, то і я пішла. Та бо я все плачу, ти знаєш. Мали були у костюмчиках, мала — з бантиками. Але до сегорічного вересня хтось більше не має костюмчика. А хтось не має чим плакати. А хтось більше не має внуків. Боже, Боже. Не кажи, не кажи, де ти є. Але чи там, де ти є, вже починались дощі? У нас вчора падав, але не сильний. Такий легенький дощик. Такий легенький, що можна брати дитину за руку і йти з нею вздовж дороги. * * * Ми знову сперечалися, коли тебе зустрічати. Але, знаєш, і 25-го, і 7-го Вифлеєм обстрілювали й бомбили. Нема ясел, нема ягнят, нема перинатального центру, нема дитячого садочка, нема дитячого майданчика. Коли ти підростеш і вже говоритимеш, скажи своїй мамі, хай скаже моїй, як їй все це пережити. Кірюха Не казатимеш: були тут. Тулились один до одногого у відбитих руских бліндажах. А сніг вже був потім. Ми були тут, але нас ніколи про це не спитають. І тільки Кірюха, наш син полка (як вона говорила), наше єдине дитя на всю вулицю, пригадає колись надломлені снікерси і мороз страшного воєнного грудня. Готуйся, питатимуть інше, готуйся. Де твоя нога? Де твої радісні друзі? Де твоя молодість, стара двадцятирічна людино, якій досі сняться смерт і надломлені снікерси? І не спитають лише головного. Де ти був, коли Миколай страшного воєнного грудня поклав біля ліжка Кірюхи кульок з «Чудо Маркету», а там були наші снікерси і мандарини. З кісточками, але солодкі. * * * Побачив, що ваза зі свіжими квітами впала. «Зараз поправлю», — кажу до фотографії на хресті. Підняв вазу, а там записка. «Зайчик, з річницейю нас. Кохаю». Ізюмське причастя ...це є Тіло Моє, що за нас ламається на на відпущення гріхів. З тексту Божественної літургії Це є тіла наші, що за нас ламаються. Але жодного відпущеня гріхів. Це є тіла наші, що, буває, так легко ламаються, коли їх витягують з-під землі. Тут наші ліси, а тут — наші хрести. А ц є тіла, що тільки за нас ламаються. Тепер добре бачиш: ми як твій син. Тільки жодного відпущення гріхів. Слухай: той самий крик, те саме мовчання. Так виглядає ізюмське причастя. Тут наші ліси, а тут — наші хрести, а живі викопують мертвих і говорять: це наші тіла, це ж наші тіла. Ми такі схожі на твого сина. Це наші тіла, подивися, це ж наші тіла. Ми вже давно як твій син. Стілки тіл, подивись, стільки тіл. Ми — твій молодший син, який нікому цього не відпустить. * * * , але чому ти так мене називаєш? Запитає вона. Чому називаєш мене містом? Ти постійно пишеш про місто, а я знаю, що це про мене. Пишеш про маршрутки, а у мене рука починає свербіти. Пишеш про вокзали, а я прокидаюсь серед ночі і більше не засинаю. Пишеш про бруківку, а я відчуваю, як не можу відкашляти клубок у горлі. Так добре було б дізнатися, чому ти називаєш мене містом. Коли вона хмуриться, то над бровами у неї з’являються ледь помітні трамвайні колії. Так добре було б не виходити на кінцевій. Діти Коли ми говоримо про надію, то насправді ми говоримо про дітей. Я вдячний, бо пам’ять про тебе досі вилазить зсередини, хоч стільки часу минуло. І колись усі діти будуть жмуритися від сонця. А ті з нас, хто виживе, побачать, що все це було не дарма. Ми тут рідко говоримо про надію, чи про патріотизм, чи про Батьківщину. Але якщо говоримо, то це завжди про дітей. І, знаєш, коли я думаю тепер про тебе, то уявляю, якою дитиною ти була. Як ти жмурилася від сонця. Ті з нас, хто виживе, будуть довго мовчати. Бо навіщо слова про надію, коли ось вна поруч. Стоїт у замурзаних шортах, чухає руки, обкусані комарами, показує сонцю молочні зуби.

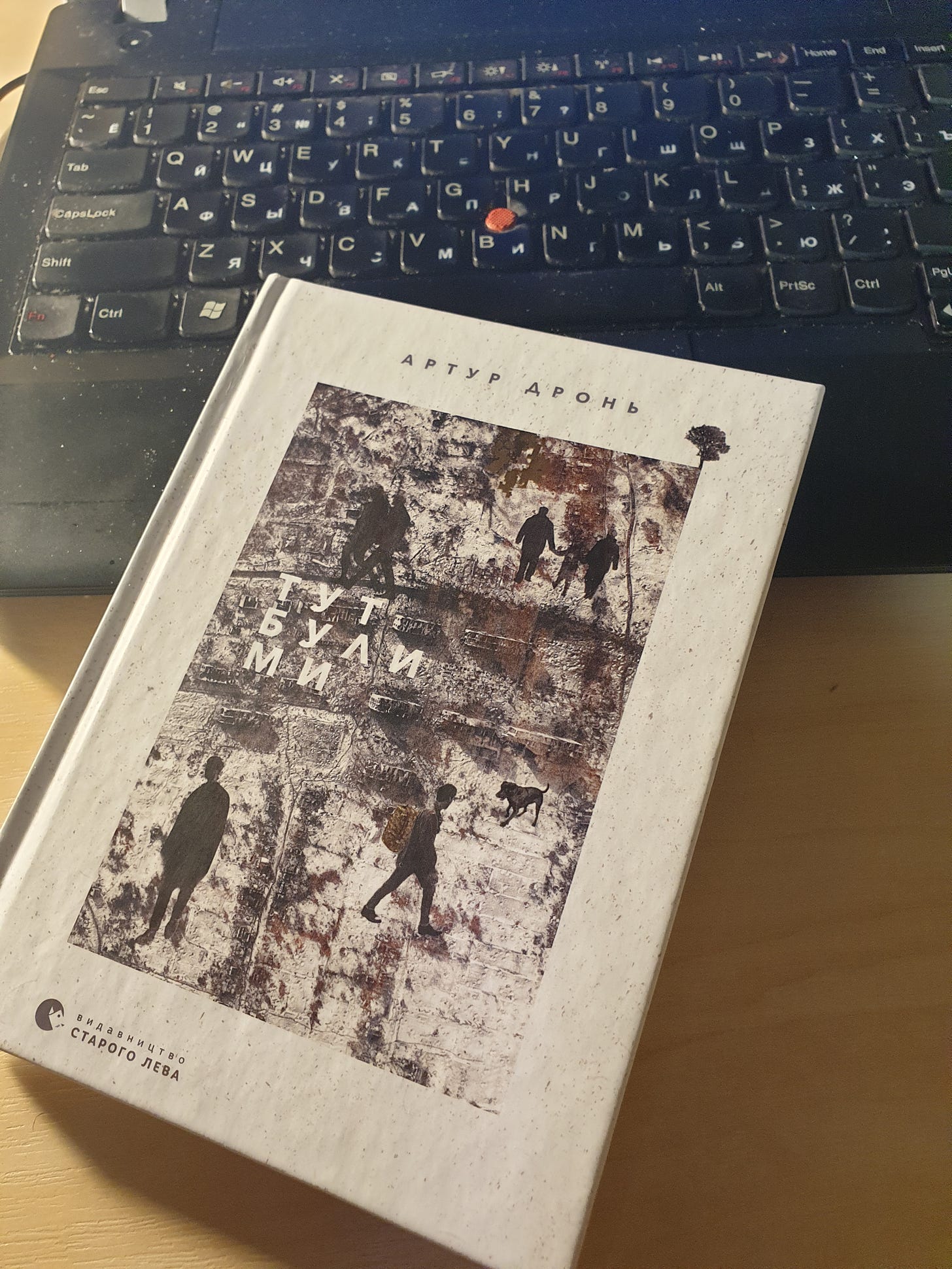

All poems are from my copy of the book “We Were Here”